‘Clothes make the man [woman]. Naked people have little or no influence on society.’ Mark Twain

I’m ten years old, in choir practice in the school hall. In the back row because I’m a head taller than the other girls, ‘outgrowing my strength’ as they used to call it. This means that, standing up, singing at full throttle, in about 30 minutes I’ll start to feel faint. This happens most weeks. My hand will go up and the teacher will run to catch me as I go.

Right now, with glances stolen away from the conductor, I’m contemplating the back view of Sandra Brown. In particular, Sandra Brown’s boots, ‘Girls’ Fashion Boots’ as they were then classified. Knee high, caramel coloured, hugging her calves like nutshells, a strap and buckle across the ankle. Those boots are what I’ll see as I hit the floor.

Sandra Brown is the girl all the boys want to kiss. She is small, blonde, compact, she sways seductively as she walks and has a look in her eyes that seems already knowing. She has a short skirt well above the knee, and just below her knees are the caramel boots. I crave them.

That same year, at Christmas, I am cast in the school play based on a Spanish folklore story, as a wealthy lady who gives away money to village folk. A week before the performance I’m informed that I won’t be playing the part of the rich lady, but will instead be a peasant. Sandra Brown will take the part. I am devastated. Wrapped in a shawl and shapeless long skirt, I watch Sandra parade around the stage dispensing largesse to us, the grateful peasants. The costume she is wearing fits her perfectly, a flounced flamenco style dress with a nipped in waist, in deep crimson. It dawns on me later that the re-casting had coincided with the arrival of the costumes, the tiny red dress among them.

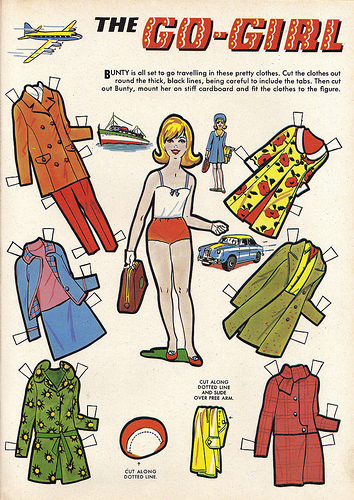

I was brought up in a family with a strange attitude to fashion and style. It stemmed from being both broke and snobbish. My parents were poor as church mice, having been struggling actors, but my mother’s family carried the social attitudes of the comfortably off upper-middle class. According to my great aunt, practically everything was ‘common’, including I recall sunglasses, sleeveless dresses, bikinis, long boots, sports cars, men with moustaches and of course mini-skirts. In fact the entire sixties as a decade was common. This had rubbed off on my mother who certainly thought that dressing children in anything that they might want to wear was an unnecessary expense and besides, probably common. Because of my growth spurt, everything was bought to ‘grow into’. Hence, my sister and I spent the sixties miserably garbed in a ghastly array of hand-me-downs and enormous school uniforms. No (common) Fashion Boots for us, in winter I had two footwear choices : a pair of sensible school lace-ups or a pair of ‘snow boots’ – ankle length zip up suede, which might sound quite trendy now, but in 1967 were worn only by septuagenarians.

This explains why, ever since leaving home, I have had an addictive relationship with clothes. Footwear in particular. The feeling of happiness when I buy, each winter, a new pair of boots is indescribable. I’m still looking for the blood-rush those caramel boots would have given me, and each pair I own fulfils something deep inside me. I have a wardrobe stuffed with clothes, half of which I never wear, but when I come home with something new I believe at that moment it will change my life. The fact that when it actually comes to going out, I have nothing to wear that seems appropriate for the particular occasion (somehow I’ve just never found the right time for that cropped fluffy jumper), could be down to consistently buying unsuitable clothes as a subconscious finger in the air to Great Aunt Hilda.

Over recent months I’ve been working with a good friend Gill Thewlis, who is setting up a new venture. Gill had an executive career in banking before deciding to do a degree in fashion design. She’s also an executive coach. She’s combined these skills and experiences to develop a concept which fuses coaching and tailoring : Your Ultimate Working Wardrobe. It’s based on the assertion that almost all professional women go to work in clothes that don’t help them perform at the top of their game, whatever that game might be. Off the peg garments, especially those with an element of tailoring such as suits and dresses, are made to fit the average shape of a woman of a size 12 or 14 or 16 etc. This means that only a tiny percentage of women within each size group actually fit the paradigm shape to which the garment is made. So they’re tight across the bum, or baggy round the tits, or narrow on the shoulders or the waist is too high or too low. The many and various ways in which clothes don’t quite fit are endless, as Gill pointed out to me one afternoon when we went through my wardrobe working out why I had so many clothes and so few that actually make me feel good.

I’m lucky enough to be one of Gill’s ‘Guinea Pigs’ (or Ambassadors as we prefer to call it, with its associations of Ferrero Roche rather than pet-wheels). I’m a bit of a challenge because I don’t work in an organisation as such and spend a lot of my working life at home wearing track pants and fluffy slippers. I work in the arts, so I dress creatively in a sometimes scruffy, sometimes smart sort of way. Part of the process has been working out just what it is about me that I want to project through my clothes.

For somebody with a sartorially deprived childhood and dysfunctional relationship with clothes, this has been a powerful, confusing and liberating experience. I’m thinking about clothes as self expression ; I’m glitching out the matriarchal voices of yesteryear telling me that clothes are common, and quelling in myself the rebellion against them usually played out by heading for the mini dresses in Primark intended for fifteen year-olds.

Just before Christmas, Gill finished my first dress. It was a simple cut, sleeveless, royal blue, great under a jacket or on its own. It was a press night sort of dress, so I wore it to a press night.

When I wore it I had an unusual sensation. The space inside the dress was the same shape and dimensions as the space my body took up. I wasn’t wearing it, I was just in it. I didn’t feel like I was too large, there was no tightness to stand in pinching judgement on the size of my waist, no bagging neckline to remind me that my bust was somewhat lower than the notional woman for whom the dress was designed. I felt like I could do things for real in that dress, it was my friend and my supporter. It was on my side. Go Tessa. Go Blue Dress.

We all have our body hang-ups. Most of my life I’ve felt too big. Tall, and clumsy, I longed to be a tiny compact person in caramel boots. Nowadays I feel better about my height. For a start, I can see the stage at gigs. On a good day I feel amazonian rather than gawky. Going through life feeling like you take up too much space gnaws at self belief, and having clothes that remind you by stretching and tightening and riding up at every step that you don’t fit the paradigm shape is exhausting. A dress which fits is much more than just a dress – it’s a kind of self activation.

Gill’s making me another dress. When it’s finished I intend to stride out throwing money at peasants.